Wytham Woods Great Tit study celebrates 75 years: Part 2 - Present

On the 27th April, 1947, the year’s first great tit egg in Oxford University’s Wytham Woods was counted. It was the start of a deep and ongoing relationship between the bird population and generations of researchers.

Seventy-five years later, 2022, the year’s first great tit egg was counted on the 28th March - almost exactly a month earlier than its 75-year predecessor.

The Wytham great tit study is the longest continuous study of an individually-marked animal population in the world. It plays a key role in scientists’ understanding of how populations change in response to the environment – particularly how they are coping with changing climates.

Sir David Attenborough said:

"I am delighted to hear of the 75th anniversary of the long-term Great Tit study in Wytham Woods. Having visited several times, I know how fundamental this study, and others like it, have been for our understanding of the impacts of climate change on the natural world. Long-term studies like this require long-term commitment, and I wish the study - and its practitioners - a long and productive future."

This week we’re marking the 75th anniversary of this one-of-a-kind research study with a three-part blog series exploring the history of the study, what’s happening there today, and what the future holds for the ‘laboratory with leaves’.

Anett Kiss (2022)

What are researchers up to?

Checking on the great tits

Andrew Harrington (2020)

The great tit study is unique system with a unique history. Its continuity and depth over time is allowing researchers working there today to explore some of the most fundamental and urgent questions in evolution and ecology.

The five most significant discoveries from the Great Tit study over the last 75 years:

- Climate change is having clear effects on familiar biological systems

- Birds adjust their behaviour, and reproductive decisions, so that they produce optimal traits for their specific circumstances

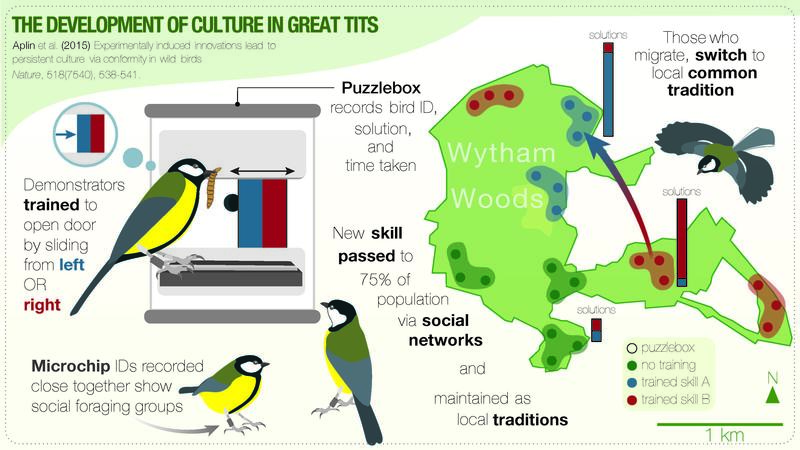

- Individual birds can learn complex behaviours from each other, and this can lead to the emergence of cultural differences

- Evolution can occur over surprisingly small scales in space and time, even in birds

- Social networks connect birds across the whole population, but individual birds adopt very consistent positions in those social networks

“In the late 1960s, when I started my DPhil on the population dynamics of Great Tits in Wytham, there was a remarkable ‘long-term’ record of the population, which I analysed to understand what factors determined the number of birds in the population. At that time ‘long term’ meant about 20 years. Now, thanks to the foresight of successive Directors of the Edward Grey Institute, and generations of DPhil students, there is truly unique record which will continue to yield novel and important insights into the ecology and behaviour of bird populations in the wild.”

Professor Lord John Krebs FRS

Read on to find out more about the ground-breaking work being done at the Wytham Woods tit study, and the people involved.

Climate change shifts the timing of spring

Using tit breeding records that have spanned the last 75 year, researchers have shown that the tits are now laying about 2 weeks earlier than they did in the 1960s, which lines up with the changes in seasons that have resulted from climate change.

However, recent research has revealed that this shift in the timing varies considerably across the woodland. Some nesting sites have advanced their egg laying by only 7.5 days, whilst others have advanced by a staggering 25.6 days. This variation is linked to the health of nearby oak trees. Birds breeding in areas with healthy oaks have advanced their laying by more than those breeding in areas with unhealthy oaks.

Anett Kiss (2022)

Other current research focuses on understanding the complex interactions between trees, caterpillars, and tits to shed light on how birds time their breeding attempts. The consequences of these decisions may vary depending on the local environment and at different spatial scales.

For example, DPhil student Anett Kiss researches the costs and benefits of these environmentally-related breeding decision adjustments (such as laying initiation, incubation duration, clutch size). She quantifies the extent of flexibility in the timing and duration of the bird’s reproductive stage. By examining how different life-history traits might adapt at the same time or pace, she hopes to develop new ways of predicting the ecological and evolutionary consequences experienced by tits in the face of climate change.

Researchers are also interested in the extent to which birds may use social information to time their breeding. DPhil student Carys Jones’ research considers the social and spatial elements that affect these changes in the timing of egg laying (among other traits) within the great tit population. She hopes that this approach will help to better understand the consequences of responses of seasonal behaviours to environmental change.

Social processes in evolutionary ecology

How individuals interact with one another is likely to have important consequences for their lives. Through tracking the activity and movements of thousands of individual birds in Wytham, researchers can monitor the social interactions within winter feeding flocks.

Dr Josh Firth with some of the 'smart feeders'

Sam Hobson (2020)

They do this using “smart” bird feeders, which are put up in the woods and open for two days a week. Each feeder scans birds wearing a digital tag. This gives a snapshot of who is feeding with whom, showing how individuals differ in their social behaviour and who they form strong social bonds with.

Dr Josh Firth, a BBSRC Discovery Fellow, conducts field experiments such as using “selective feeding systems” that allow the automatic control of which birds are allowed to feed together. Using this approach, they have shown that social connections formed during foraging carry-over into other contexts, and also that mated pairs who hold strong social relationships will shape their activity, social network position and foraging strategies around each other.

Others are using the Wytham tit study to understand other social behaviours of the great tits, and their consequences. DPhil student Samin Gokcekus is looking to understand how and why cooperation arises, and how it is maintained in social networks. Joe Woodman, another DPhil student, focuses on how age is distributed across the great tit populations, and what ecological and social effects that might have.

“The breeding season fieldwork also allows you to observe unique situations which you would otherwise be unaware of, for example last year I caught a male at three different boxes that was simultaneously raising three broods with three separate females”

Joe Woodman

Anett Kiss (2022)

Bird diseases: malaria and avian pox

Recently, researchers look at the way that infectious diseases spread among, and affect, the different tit species in the woods.

One disease that some find surprising to learn infects birds in the UK is malaria. Far from being a largely tropical disease as in humans, avian malaria can be found in birds in very many parts of the world. The avian malaria parasite - Plasmodium - is quite closely related to the parasites that cause human malaria. Focussing particularly on blue tits, and to a lesser extent on great tits, they have explored the spread, timing and effects of malaria infections in birds.

A juvenile great tit with avian pox

Jenny Davis (2018)

One surprising finding is that, for tits in Wytham, whether they are infected depends hugely on where they live. There are parts of Wytham where fewer than 10% of birds are infected and other parts where more than 80% are. This variation occurs over short distances: as little as 1 km separates the areas with highest and lowest infection rates. Our best hypothesis for the cause is that it reflects the distribution of the bird-biting mosquitoes that spread avian malaria.

In 2009 there was a novel outbreak of avian pox among the birds at Wytham. Infecting mostly great tits (and to a lesser extent other tit species), and by 2010 almost 10% of birds showed symptoms. Our studies, which were aided enormously by records from the public of birds in gardens, documented the spread of this disease as well as showing that it had serious effects for infected birds.

With 75 years of history, and a breadth and depth of boundary-pushing ongoing ecological and evolutionary research at Wytham, what does the future hold for the laboratory with leaves?

Read Part 3 of the Wytham blog series to hear about the future of the project

Meet some of the people working on the incredible Wytham Tits project:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/WKW8WvMPjvw