Wytham Woods Great Tit study celebrates 75 years: Part 1 - Past

On the 27th April, 1947, the year’s first great tit egg in Oxford University’s Wytham Woods was counted. It was the start of a deep and ongoing relationship between the bird population and generations of researchers.

Seventy-five years later, 2022, the year’s first great tit egg was counted on the 28th March - almost exactly a month earlier than its 75-year predecessor.

The Wytham great tit study is the longest continuous study of an individually-marked animal population in the world. It plays a key role in scientists’ understanding of how populations change in response to the environment – particularly how they are coping with changing climates.

Sir David Attenborough said:

"I am delighted to hear of the 75th anniversary of the long-term Great Tit study in Wytham Woods. Having visited several times, I know how fundamental this study, and others like it, have been for our understanding of the impacts of climate change on the natural world. Long-term studies like this require long-term commitment, and I wish the study - and its practitioners - a long and productive future."

This week we’re marking the 75th anniversary of this one-of-a-kind research study with a three-part blog series exploring the history of the study, what’s happening there today, and what the future holds for the ‘laboratory with leaves’.

How it all started

Wytham Abbey before it was gifted to the University

Wytham Woods was gifted to the University by the ffennell family in 1942 after the death of their only child, Hazel. The ffennels requested that the woods be used "for the instruction of suitable students" and to "provide facilities for research". The woods have since become the University's ecological laboratory. Scientists use the woods to research environmental change, conservation, palaeoecology, long-term vegetation change, community ecology, and the behaviour and ecology birds, bats, badgers and rodents.

In 1947 John Gibb and David Lack – after newly joining the Edward Grey Institute of Ornithology after the Second World War – identified the potential of Wytham Woods to study the breeding biology of the great tit.

Why were ornithologists at Oxford so interested in great tits?

David Lack

Great tits are an excellent study species for ecological research as they readily take to nest boxes, breed at high densities, do not travel far from where they are born, and cope well with being monitored by scientists. This means they can be individually tagged in large numbers with unique leg rings, and can then be followed throughout their lifetimes.

John, David, and their team initially put up 100 nest boxes in Marley Wood, one section of Wytham Woods. The study was later expanded in around 1960 to cover the entire 385-hectare woodland using over 1,000 fixed location nest boxes.

During the last 75 years, researchers have monitored all the breeding attempts in these boxes and individually-identified all parents and their offspring – which now spans over 55 generations.

“In 1962 we planned to extend the area covered by nest-boxes to include the Singing Way, but we didn’t allow for the very hard winter; the snow started on Boxing Day 1962 and continued through into March; we even got a Land Rover stuck in a snow rift while trying to get along the Singing Way with a load of boxes.”

Professor Emeritus Chris Perrins

Seeing evolution in action

One of the first and most significant series of findings to emerge from the great tit study was how birds adjust their behaviour and breeding decisions in response to specific circumstances.

By studying the great tit population at Wytham Woods, biologists were able to show that there was an optimum number of eggs to lay based on the availability of food (such as insect larvae) during the breeding season. If birds laid on average more than this number, this would result in fewer surviving young because their resources are stretched beyond what the habitat can support.

This combination of theory and data laid the foundations for a principle of natural selection that applies beyond just this population of great tits. Many reproducing organisms seem to have an optimised number of young. The pioneering work started at Wytham Woods led to an improved understanding of the mathematics of natural populations.

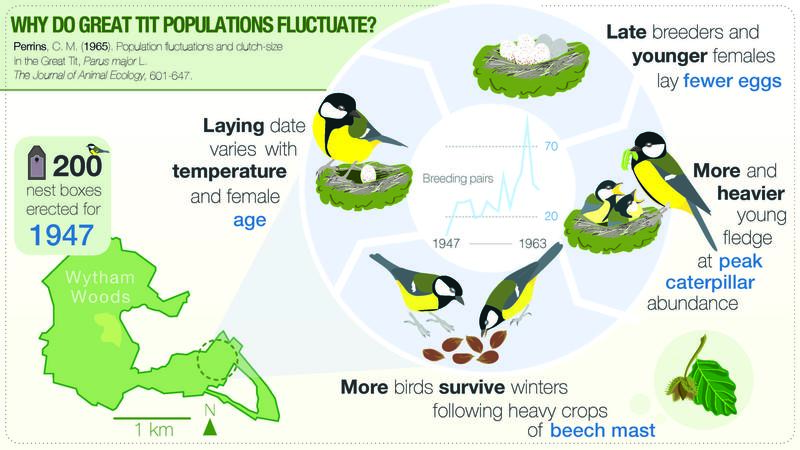

Another significant discovery from the great tits at Wytham Woods was that evolution can occur over surprisingly small scales in space and time. For example, in 1965 Chris Perrins showed how changes in the size of the tit population was sensitive to spring temperatures, food availability over the winter, female age, and caterpillar abundance.

Anett Kiss (2022)

Spring timing in the face of climate change

As the volume of data from the study increased, as well as the perspective through time it offered, it became possible to examine the effects of climate change on the great tits.

The timing of the laying of Great Tit eggs is intricately linked to the health of nearby oak trees, which researchers now understand in terms of potential vulnerabilities and resilience to changing climates.

Professor Ben Sheldon, who leads the Wytham Great Tit study, said:

‘A study of this duration outlives the scientists who work on it, and it’s been a great privilege to follow in the footsteps of world-leading ornithologists from the past, and the hundreds of people who’ve ensured the study worked, year in, year out.

‘That continuity has enabled us to make use of the full span of 75 years’ data to understand how changes occur over time. One of the clearest and most striking changes is that the average Great Tit breeds three weeks earlier now than it did at the start of the study.

‘This shift is a clear signal of the effects of climate change on one of our most familiar woodland and garden birds, and it is studies of this kind that allow us to work out what the consequences of such changes have been, and may be in the future.’

Ben Sheldon

The great tit study’s unique system and history, with its continuity and depth over time, is allowing researchers working there today to explore some of the most fundamental and urgent questions in evolution and ecology.

Read Part 2 of the Wytham blog series to hear about the project in the present day

Meet some of the people working on the incredible Wytham Tits project:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/WKW8WvMPjvw