Wytham Woods Great Tit study celebrates 75 years: Part 3 - Future

On the 27th April, 1947, the year’s first great tit egg in Oxford University’s Wytham Woods was counted. It was the start of a deep and ongoing relationship between the bird population and generations of researchers.

Seventy-five years later, 2022, the year’s first great tit egg was counted on the 28th March - almost exactly a month earlier than its 75-year predecessor.

The Wytham great tit study is the longest continuous study of an individually-marked animal population in the world. It plays a key role in scientists’ understanding of how populations change in response to the environment – particularly how they are coping with changing climates.

Sir David Attenborough said:

"I am delighted to hear of the 75th anniversary of the long-term Great Tit study in Wytham Woods. Having visited several times, I know how fundamental this study, and others like it, have been for our understanding of the impacts of climate change on the natural world. Long-term studies like this require long-term commitment, and I wish the study - and its practitioners - a long and productive future."

This week we’re marking the 75th anniversary of this one-of-a-kind research study with a three-part blog series exploring the history of the study, what’s happening there today, and what the future hold for the ‘laboratory with leaves’.

The next 75 years of Wytham

What will the next 75 years look like for the Wytham tits?

Andrew Harrington (2021)

The last 75 years of the Wytham tit study have contributed some of the most important and surprising findings about ecology and evolution, as well as the continued effects of climate change on the animals and plants we share the planet with. But as ever in science, answering one set of questions creates yet more to be answered.

The top five unanswered questions for the Great Tit study over the next 75 years

- Where do birds that leave the Wytham population go to, and where do birds that come into the population come from?

- What sense do individual birds have of each other’s identity?

- How do birds manage the challenge of responding simultaneously to large and local scale environmental change?

- What is the basis of 'individual quality' between different birds?

- How robust is the Wytham system to the climate change that we expect to see in coming decades: will our current understanding prove to be accurate?

“There is plenty that we still need to understand about the current populations. But we can be confident that the changes which are already happening will give us the opportunity to contribute valuable information to the world. Climate change is now a household term, and we know that the tits are already responding by breeding earlier than they used to. The woods themselves are also going to change, we stand to lose all or most of the ash trees in the next decade and oaks are dying faster than they used to”

Professor Emeritus Chris Perrins

What new directions and challenges lie in store for the tit study?

The changing climate and ecosystem

Researchers say they know that climate change is driving large scale changes in the timing of seasonal events, affecting plants and animals across the globe. But researchers at Oxford are keen to know - how much does this matter for the survival and reproduction of these organisms, and ultimately how they will be affected by climate change?

Ella Cole (2021)

Oxford’s researchers are aiming to work out how much birds are influenced by effects at small and large scales, and how these interact with and impact ecological networks. New research, funded by an ERC Advanced Grant awarded to Professor Ben Sheldon and announced earlier this week, aims to combine measures of the timing of ‘leaf-out’ for hundreds of thousands of trees across Wytham Woods, with data on insects and birds that rely on these trees for food.

New tools and new connections

Continued funding through grants supports the design and implementation of novel ways of carrying out research. This involves using new tools and forming new international connections and collaborations.

The Wytham tit study has recently become part of the SPI-Birds Network & Database, a pan-European cooperative initiative among ornithologists who collect data on individually-marked breeding birds. The network acts to connect researchers up who are monitoring population long-term, as well as existing projects. Because the Wytham tit study is the longest running of its kind, it forms an integral part of the network.

“Increasing the extent of larger-scale linkups within and between other long-term studies – such as through the SPI-Birds Network- using similar methods in other European countries means we can ask larger-scale questions about birds across the continent”

Dr Ella Cole

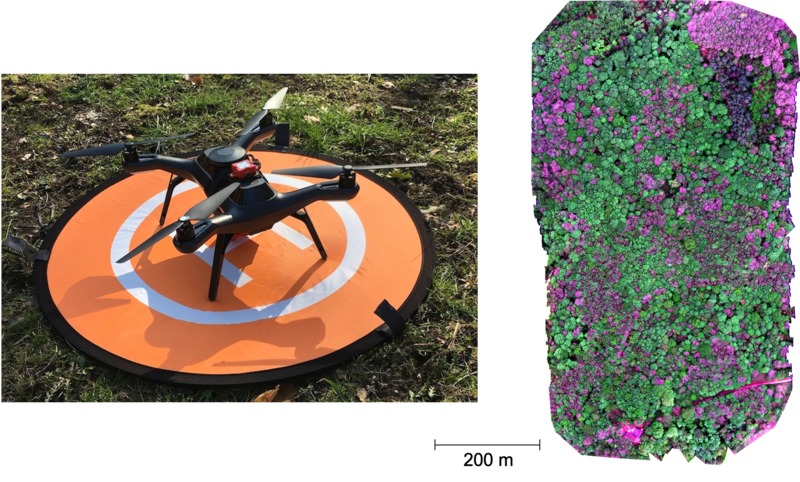

Some of the new suite of tools that researchers are a kind of drone called unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVS) in combination with artificial intelligence (AI). The caterpillars that the great tits eat feed on the leaves of deciduous trees, like oaks. The timing of the peak in caterpillar availability for great tits is largely determined by when the deciduous trees come into leaf. If researchers can more accurately measure the timing of leaf emergence of the trees, they can better understand how climate change is affecting how birds time their egg laying relative to the local environment.

The kinds of drone the team plan to use, and an example of the AI image of Wytham's canopy

Ella Cole (2022)

However, they need to measure tree leaf emergence at a small enough scale to be relevant to the biological processes they’re interested in, while simultaneously doing it at a large enough scale in space and time to make the results reliable and valid. This is huge challenge, but drones and AI are one solution.

Ground-based observation of ecological changes such as leaf emergence generates only a tiny fraction of the data needed to understand the responses of the whole ecosystem at multiple scales. Researchers like Dr Ella Cole plan to use drones to collect large-scale high-resolution data about Wytham’s trees. By flying drones carrying cameras capable of seeing different kinds of light over the woodland every few days, they hope to calculate the bud-burst date of each tree. This will allow them to quantify how individual birds experience and respond to changes in the trees and caterpillars. Extracting the data from the images will require sophisticated computational methods. They hope to develop and apply neural network methods to create an analytical framework that will allow them to separate out the crowns of individual trees, identify which tree species they belong to,

Long-term studies require long-term funding

Grants such as the prestigious ERC Advanced Grant make an important contribution to answering these questions, but long-term studies require long-term funding. The researchers based at the Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology hope that the next 75 years of study will be as productive and influential as the first 75 years.

Meet some of the people working on the incredible Wytham Tits project:

https://www.youtube.com/embed/WKW8WvMPjvw