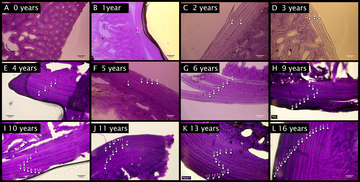

Overview of stained sections of hedgehog jaws, showing year rings which allows the researchers to determine the age of the hedgehogs

Image: Thomas Bjorneboe Berg

The European hedgehog is one of our most beloved mammals, but populations have declined dramatically in recent years. To combat this, researchers and conservationists have launched various projects to monitor hedgehog populations, to inform initiatives to protect hedgehogs in the wild. These include “The Danish Hedgehog Project”, a citizen science project led by Dr Sophie Lund Rasmussen.

During 2016, The Danish Hedgehog Project asked Danish citizens to collect any dead hedgehogs they found to better understand how long individual Danish hedgehogs typically lived for. Over 400 volunteers collected an astonishing 697 dead hedgehogs originating from all over Denmark, with a roughly 50/50 split from urban and rural areas.

The world’s oldest hedgehog

Dr Sophie Lund Rasmussen looks in a microscope

Image: Thomas Degner

The research team determined the age of the dead hedgehogs by counting growth lines in thin sections of the hedgehogs’ jawbones – a method similar to counting year rings in trees. During hibernation, bone growth is reduced markedly or even stopped. This causes the bone to become denser, resulting in growth lines where one line represents one hibernation.

The results showed that the oldest hedgehog in the sample was 16 years old - the oldest scientifically documented European hedgehog ever found, and 7 years older than the previous record holder, which lived for 9 years. Two other individuals lived for 13 and 11 years respectively.

But despite these long-lived individuals, the average age of the hedgehogs was only around two years, and about a third (30%) of the hedgehogs died at or before the age of one year. Over half had been killed when crossing roads, others at a hedgehog rehabilitation centre (for instance, following a dog attack) or of natural causes in the wild.

The research also showed that male hedgehogs in general lived longer than females, which is uncommon in mammals. Male hedgehogs were also more frequently killed in traffic, especially in rural areas and during the month of July, which is the peak of the mating season for hedgehogs in Denmark. Dr Sophie Lund Rasmussen said:

The tendency for males to outlive females is likely caused by the fact that it is simply easier being a male hedgehog. Hedgehogs are not territorial, which means that the males rarely fight. And the females are raising their offspring alone. Sadly, many hedgehogs are killed in traffic each year, especially during the mating season in the summer, as the hedgehogs are walking long distances and are crossing more roads in their search for mates.

Inbreeding does not appear to affect longevity in hedgehogs

The researchers also took tissue samples to investigate whether the degree of inbreeding influenced how long European hedgehogs live for. Inbreeding can reduce the fitness of a population by allowing hereditary, and potentially lethal, health conditions to be passed on between generations. Surprisingly, the results showed that inbreeding did not seem to reduce the expected lifespan of the hedgehogs. Dr Rasmussen said:

Sadly, many species of wildlife are in decline, which often results in increased inbreeding, as the decline limits the selection of suitable mates. Our research indicates that if the hedgehogs manage to survive into adulthood, despite their high degree of inbreeding, which may cause several potentially lethal, hereditary conditions, the inbreeding does not reduce their longevity. That is a rather groundbreaking discovery, and very positive news from a conservation perspective.

To read more about this research, published in Animals, visit: https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13040626.