While cells naturally divide in healthy tissues to replenish or repair the body, cancers develop from uncontrollable cell division. Larger and longer-lived animals have more cell divisions, suggesting that they are more likely to develop cancer than smaller animals – but this does not seem to be the case.

Elephants, like Ndeke pictured here in Samburu National Reserve, Kenya, have 20 copies of a gene commonly associated with preventing cancer by detecting and disabling damaged DNA.

Image: Jane Wynyard / Save the Elephants

With the discovery of a genetic marker, elephants have become a focal species to analyse this puzzling phenomenon, also called Peto’s Paradox. This marker is the TP53 gene, encoding the p53 protein – which has become famous for its ability to detect and disable damaged DNA during cell divisions, therefore preventing mutations from spreading. Elephants uniquely have 20 copies of this gene while, as far as we know, all other animals have only one copy.

A new theory suggests that the surprising multiplication of these genes would have evolved not to fight cancer, but instead to stabilise DNA in sperm cells. Evolution in tissue cells is slow, and developments that happen in older age when the animal has produced most of its offspring have much lower selection pressure acting on them. In contrast, selection on egg and sperm cells is much stronger and faster because it interacts so directly, with life and death always in the balance for each single cell. The theory suggests that the genes are therefore more likely to have evolved for a purpose associated with the reproductive cells – but that this has provided important collateral benefits associated with cancer as well as ageing.

The author of this study, Professor Fritz Vollrath from the Department of Biology at the University of Oxford, and the chairman of the UK charity Save the Elephants, said:

Elephants are providing us with a unique system to study the evolution of a powerful defence against DNA damage, and to explore the intricacies and details of the p53 complex in our own fights against cancer, ageing and even, as it turns out, male reproductive health.

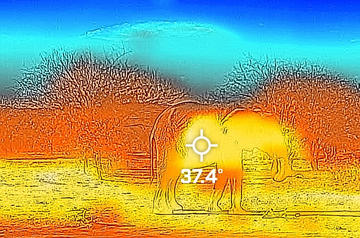

A young elephant captured by a FLIR camera false colour temperature image with the area of the crosshairs indicating the skin temperature. The air temperature was 28.6°C with the ground still hot (yellow) in places although the sun has just set

Image: Fritz Vollrath

Professor Vollrath has developed this theory by combining his insights of elephant behaviour, ecology, and evolution. In most mammals, the production of healthy sperm relies on the testes being several degrees below the animal’s body temperature. However, elephants lack the ability to descent their testicles, which therefore remain buried inside the body. This has consequences on the production of healthy sperm, as the testes are at the same high temperature of the body. Additionally, elephants tend to have a high body temperature due to their large body size in comparison to their surface area, enhanced by thick skin and a blood heat exchange mechanism limited to blood flow in the ear flaps. Consequently, in a bull running, climbing, or fighting, body temperatures can reach levels that are dangerously high for any mammal’s metabolism and impossibly hot for the production of healthy sperm. Here, the famous p53 protein would weed out developing sperm with damaged DNA. Evolving more than one copy of the gene, as found in elephants, would allow for modifications of the protein, creating a larger genetic inspection ‘toolbox’ and magnifying the detection of mutations in any DNA scanned, be it in sperm or cancer cells.

Investigating how these proteins act to protect cells and tissues will be a key step in the discovery of ways and means to combat cancer, as well as shedding light on the intriguing questions linking testicle temperature and reproductive health.

To read more about this research, published in Trends in Ecology & Evolution, visit: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2023.05.011