Taking advantage of crops’ wild relatives to bioengineer climate-resilient agriculture, achieve food security, and environmental sustainability

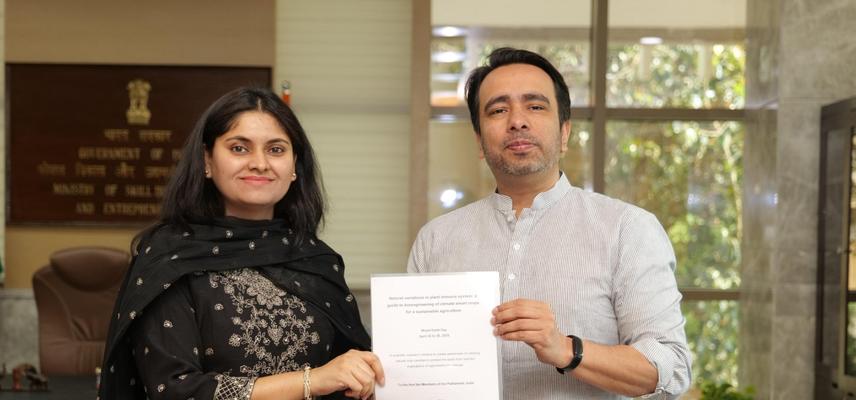

Shivani Malik, DPhil student in the Plant Chemetics Lab led by Professor Renier van der Hoorn, has been engaging with policymakers in her home country of India to share the importance of biological advances to the agricultural sector.

Growing up in a community integral to India’s agricultural economy and political landscape, I have long been interested in initiatives that can contribute to shaping the agriculture sector. Crop yields are threatened by pathogens, which commonly inhabit the space between cells in plant leaves. This space serves as a battlefield and determines the ultimate fate of host plants. Up to 40% of crop losses are estimated to be caused annually by plant diseases and pests (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2024). The overuse of pesticides compromises the ecosystem and impact species that are not the intended targets. Additionally, changing climatic conditions are triggering new plant pathogen strains and presenting a challenge to food security, sustainable development in agriculture, and agrarian-driven economic stability in countries like India.

Research – and its application – is essential to combat future plant pandemics. A useful resource for sustainable bioengineering of crops with a wider spectrum of disease resistance is finding and understanding the genetic basis of variance in plant response to pathogens. I recently submitted my DPhil thesis, where I researched the natural variation in recognition of inhibitors from several pathogens in wild populations of solanaceous crops from their centres of origin. By identifying tomato and potato populations with genetic variations involved in conferring recognition of diverse plant pathogens, our work will broadly serve as a guide for future bio-engineering research to develop durable pathogen resistance in crops.

Over the past month, I have been engaging in thought-provoking discussions with political leaders in India and emphasising the importance of making use of wild crops and next generation gene editing technology to ensure crop and environment protection while adapting to climate change. As part of the initiative, we showed how natural variations in plant immune systems in wild crop relatives are being investigated through experimental research, and explained the significance of applying genetic knowledge to reduce the use of chemical solutions and instead focus on enhancing climate-smart sustainable agriculture productivity. The impact potential of environmentally sustainable gene-editing innovations for global food security, farm, and farmer prosperity were discussed in detail.

India has dedicated the year 2025 to ‘Empowering Indian Youth for Global Leadership in Science and Innovation for Viksit Bharat* Vision 2047’, and with the recent release of two gene-edited rice varieties resistant to abiotic stressors, a new era begins in agriculture. Over the last 10 years, India’s rank in the Global Innovation Index has upgraded from 80th to 39th in 2024. This accomplishment reflects how a research and development ecosystem of international and national collaborations, increased public and private investments, and robust policy frameworks that ensure effective translation from labs to real solutions support the fostering of ground-breaking innovations. Regardless of scientific career stage, Indian-origin scientists, having benefited from research experiences at leading international institutions like Oxford, continue to play significant role in science policy advocacy. Sharing ever-changing research findings and their communication to policy makers enhances the understanding of challenges, and strengthens the intricate process of using science-based information to design and implement public policy.

Several ministers and members of parliament engaged in discussions with me, including those involved in agriculture, science, and education. Our conversations included topics such as where crops originated, cross-breeding with wild relatives, the global acceptance and regulations of gene editing, and the scope for other purposes like river restoration and the development of smart proteins.

I am truly thankful to my Supervisor, the Department of Biology, and all these political leaders for their willingness to thoughtfully (and warmly) collaborate and support this initiative.

* ‘Viksit Bharat’ refers to ‘Developed India’