Tropical forests are one of the most important habitats globally, holding over half of the world’s land animals and plants, but they are being rapidly cleared for resources like wood and space for agriculture. Many remaining tropical forests are now degraded and fragmented; this is a major problem for the animals that live in them, as their habitats are patchy and may be missing important species which contribute to the ecosystem. This has made the issue one of the biggest threats to biodiversity worldwide.

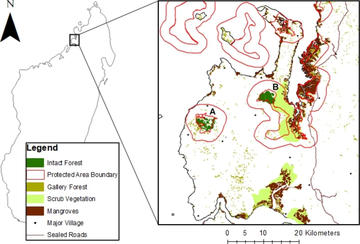

The Sahamalaza-Iles Radama National Park and the location of Ankarafa forest (A) and Anabohazo forest (B). Red lines represent the protected area boundary (inner), and a three kilometre buffer (outer).

Figure: Hending et al. (2023)

To investigate the effects of fragmentation on the trees themselves, researchers studied two transitional forests – which contain both deciduous and evergreen species, being located between tropical and subtropical – in the Sahamalaza-Iles Radama National Park in northwest Madagascar. The two forests differ in quality, with Anabohazo being continuous forest and Ankarafa being fragmented, allowing the researchers to compare the trees in each.

As well as fragmentation, they looked at its associated edge effects – which are seen at the boundaries between different types of habitats, for example forest and grassland, and often have a different community of species to core areas of a habitat type. The researchers wanted to understand the influence that fragmentation had on the trees’ size, species diversity, and structural diversity (the spacing and layering of species, which is a good predictor of ecosystem function).

After collecting data from 9,619 individual trees, the researchers found that tree size and diversity were lower in fragmented forest and edge areas in comparison to core, continuous forest. Bigger forests, and particularly bigger core areas, had more species and structural diversity. The shape of forest fragments also played a part, as longer and wider areas didn’t see as much of an edge effect. The researchers additionally discovered that fragmentation increased edge effects and vice versa, contributing to a feedback loop of a degrading ecosystem. Dr Daniel Hending, lead author, said:

The results provide us with evidence that forest fragmentation seriously degrades habitat quality and integrity of transitional forests, which is of great concern for the threatened species that inhabit them. Urgent conservation efforts are needed to halt ongoing forest fragmentation throughout the tropics, as well as reforestation and restoration to reconnect isolated patches and reduce forest edge area.

The researchers will now focus on the resident lemur communities of the two forests studied. They will explore how the population density, behavioural ecology (interactions between individuals and their habitat), and physiology of the lemurs differs with the habitat quality of the two forests, and between edge and core areas. This will allow them to bring together degradation of habitat with the direct impacts that this can have on the animal populations that live within them.

Anabohazo forest, a continuous forest within the Sahamalaza-Iles Radama National Park

Image: Daniel Hending

Ankarafa forest, a fragmented forest within the Sahamalaza-Iles Radama National Park

Image: Daniel Hending

A blue eyed black lemur, one of the species found in the Sahamalaza-Iles Radama National Park

Image: Daniel Hending

To read more about this research, published in Biodiversity and Conservation, visit: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-023-02657-0