Black History Month – A reflection on the contributions of Black Biologists

The first in our series of blogs for Black History Month 2022 looks at the careers and contributions of prominent Black biologists both past and present.

The Department of Biology is hosting a panel event, 'Being Black in Biology', on Wednesday 26th October 1:30 - 2:30pm. If you would like to attend either in-person or virtually, please register here.

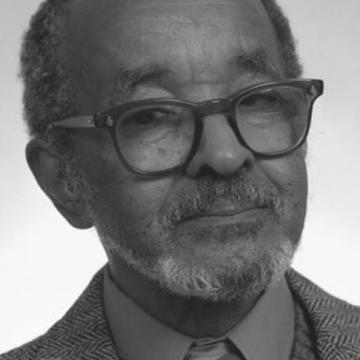

Dr Donald Palmer

Palmer is Associate Professor of Immunology at the Royal Veterinary College (RVC), and has worked primarily on how age affects the immune system, as well as how immune markers can be used to identify cancers.

Donald’s main area of research is focused on investigating the cellular and molecular interactions involved in T-cell development. In particular, his group seeks to understand the processes that are involved in age-associated immunosenescence. His group have been investigating the architectural changes in the ageing thymus gland, and made the novel finding of the presence of senescent cells in the thymus of older animals. His group has extended their to interests to the affect of ageing on other components of the immune system, such as Natural Killer cells function in elderly people.

Dr Wangari Maathai

Maathai was the first woman in East and Central Africa to earn a doctorate, and headed the Department of Veterinary Anatomy at the University of Nairobi for around thirty years, before being elected as an MP and Minister for Agriculture. In 2004, she was awarded the

Nobel Peace Prize.

In 1977 she started a grass-roots movement aimed at countering the deforestation that was threatening the means of subsistence of the agricultural population. The campaign encouraged women to plant trees in their local environments and to think ecologically. The so-called Green Belt Movement spread to other African countries, and contributed to the planting of over thirty million trees. Maathai's mobilisation of African women was not limited in its vision to work for sustainable development; she saw tree-planting in a broader perspective which included democracy, women's rights, and international solidarity.

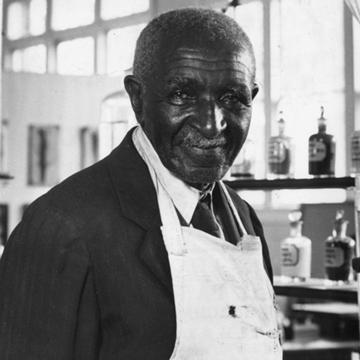

George Washington Carver

Carver was born into enslavement in Missouri, and was orphaned after his parents were kidnapped. After moving through several schools and foster families, he eventually studied

botany at Iowa State College in 1891, where he was the first Black student. Later, in 1896, he took over the Agriculture Department at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where he taught for nearly fifty years.

Carver made major contributions to agricultural science by developing new methods of crop rotation to improve soil quality in areas depleted by cotton production. The cultivation of crops, such as peanuts and sweet potatoes, acted both to restore poor soils and provide additional food for farmers and their families. After slavery was abolished in the US, Black farmers were given land that was extremely nutrient poor, so the cultivation methods that Carver helped develop and teach were of particular importance to Black growers.

Dr Emmett Chappelle

Chapelle is best-known for his work on the biochemistry of bioluminescence, developing methods for detecting bacteria, and showing that many microorganisms can carry out photosynthesis.

After working at several universities in the US in the 1950s, Chappelle moved into industry, where he discovered that single-celled organisms such as algae could be photosynthetic. The relevance of this finding to space exploration, as a means of producing oxygen and food for astronauts on missions, led to a career with NASA. Until 2001, he developed tools for sample collection on missions to Mars, remote sensing technologies, and how to detect the presence of ATP using luciferase and luciferin.

Dr Kizzmekia “Kizzy” Corbett

Corbett is an immunologist at the National Institute for Health (NIH) who co-led the team that worked with Moderna to develop the COVID-19 vaccine. After earning her doctorate in microbiology and immunology, she started at the Vaccine Research Centre at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), where she is the scientific lead on the coronavirus vaccine team.

In a recent interview with Essence, she said: “Black people are about two-to-three times more likely to die from COVID. So, as I sit here, as a Black woman and also the co-lead of the team that helped to develop one of the vaccines, it is extremely important to me to have made that history from a scientific perspective, but also to remind people how history has changed in regard to how health and science and race come together as one”

“To stand in the forefront of the vaccine development efforts—a vaccine that is 94% efficacious and has the ability to end this pandemic and be the great equalizer as we think about health disparities—it is so important and really is an honour for me.”

Why are there so few Black biologists?

In putting together a piece on the history of Black biologists, one thing that becomes clear is there are few Black academics, particularly from the UK. The short answer is that there have been and are currently few Black academics in the field of biology.

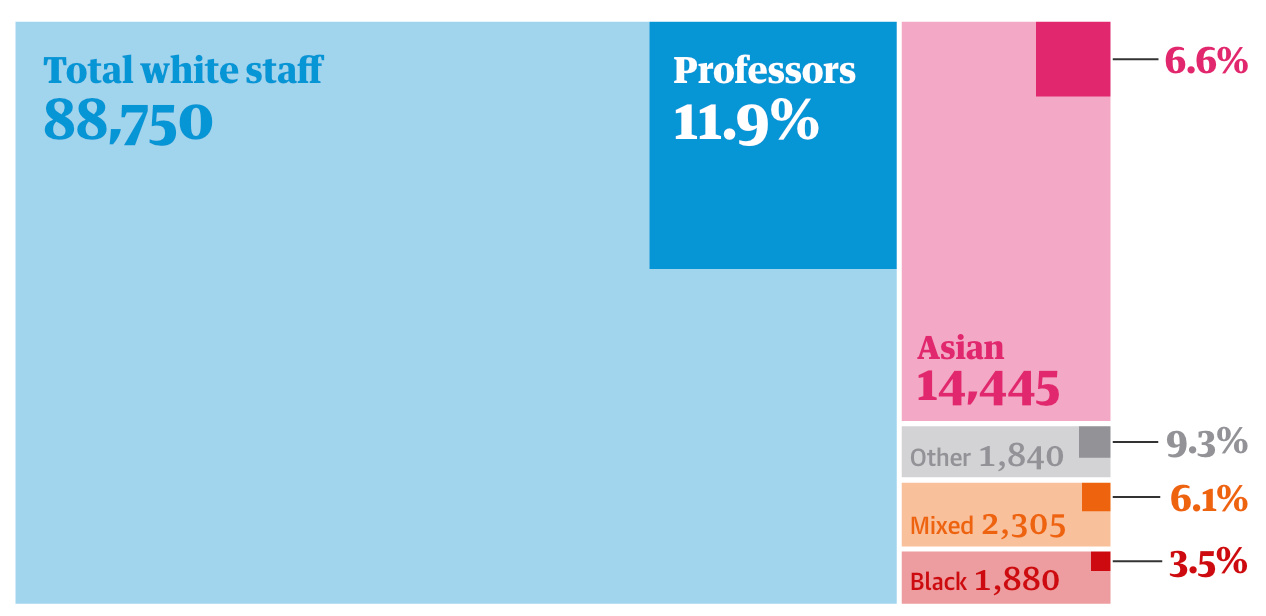

A 2020 report conducted on behalf of the Royal Society shows how under-represented Black people are in STEM in the UK, particularly at senior levels. In 2018-19, 1.85% of STEM academic staff identified as Black, with the proportion decreasing with age, suggesting that Black researchers in science are less likely to be promoted than their white colleagues. The biological sciences in particular has played a historical role in establishing the concept of race, due to associations with colonialism, scientific naming conventions, and eugenics.

Source: Guardian graphics

Here at Oxford, the Race Equality Task Force was set up in 2020 following the murder of George Floyd to oversee the active dismantling of systemic racism across the University. Many Black students and staff within STEM subjects and departments are part of the BIPOC STEM Network, which promotes and support the work of people of colour within the University and beyond, in order to create a more diverse and inclusive environment within STEM. Additionally, within the Department of Biology, work is currently ongoing to decolonise our MBiol curriculum.

It’s important to celebrate the incredible achievements of Black biologists such as those in this blog, as well as the graduates and post-docs featured as part of the Department of Biology’s campaign as part of Black History Month. However it’s also crucial to remember that the lack of senior Black researchers in UK biosciences requires continued action to support the careers of Black biologists.